RAUPE-

NIMMERSATTISM.

THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY AS CONSUMED SOCIETY OR THE MYTH OF ENDLESS PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION

research, performance, Radio and exhibition project 26.09.–22.11.2020

OPENING HOURS Thursday–Sunday 14:00–19:00

[closed from 02.11.2020 on due to new Covid19-regulations]

With Laylah Amatullah Barrayn, Lhola Amira, ArTree Nepal (Hit Man Gurung), Yasmin Bassir, Sol Calero, Mansour Ciss Kanakassy, Phil Collins, Minerva Cuevas, Sarah Entwistle, Samira Hodaei, ILYICH, Anton Kats, Cinthia Marcelle, Fallon Mayanja, Daniela Medina Poch & Juan Pablo García Sossa, Jean David Nkot, Krishan Rajapakshe, Nasan Tur and an Afropop Worldwide podcast feature

VISIT Online

Come visit the Raupe in her digital garden at raupenimmersattism.savvy-contemporary.com

(If you allow access to your microphone, you can talk with other visitors)

AUDIO TOUR

Listen HERE to a visit of RAUPENIMMERSATTISM

Kate Brehme takes you on a subjective and sensory audio tour through the exhibition. The independent curator and co-founder of Berlinklusion, Berlin’s Network for Accessibility in Arts and Culture, shares her personal response to the materiality, feel, time and evoked thoughts of this exhibition on inequalities. She invites you to ponder with her the central premise of the exhibition to challenge structural inequalities, stand alongside positions of vulnerability by connecting them also to the yawning gap between affluence and poverty impacts on human bodies and lives – especially with regards to poverty and disability. Below this grey box, you find the tour text to read along.

Kate Brehme is an Australian born Berlin-based independent curator and arts educator with a disability. She has worked internationally on a variety of projects, exhibitions and events and since 2008 runs Contemporary Art Exchange, a curatorial platform providing professional development opportunities for emerging and young artists. Her research and project themes include place and cultural identity, labour and work, globalisation, disability and socially engaged practices. Since moving to Berlin from Scotland in 2012, Kate continues to produce Contemporary Art Exchange projects and lectures for both the Master Education in Arts programme at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam and NODE Center for Curatorial Studies in Berlin. In 2017, together with Dirk Sorge, Jovana Komnenic and Kirstin Broussard, Kate co-founded Berlinklusion, Berlin’s Network for Accessibility in Arts and Culture striving to make Berlin’s arts and cultural scene more accessible for artists and audiences with disabilities.

Having moved into a new space – a former casino – that further pushes us to reflect on precarity, reckoning with the fact that we are often chips in a larger system of gambling, our first project in our new home interrogates the potentiality of the risks and realities of having to be tricksters, surviving as such. To confront the endless consumption of our societies and the affluence many hold at the expense of others’ poverty, a collective exhibition is composed as a result of ten months of research, grapplings, and reasonings together. The show unfolds as a choral questioning to challenge structural inequalities and stand alongside positions of vulnerability.

At SAVVY Contemporary, exhibition practices are always considered as spaces of research and knowledge production, exchange and dissemination, as well as spaces in which certain social norms can be challenged. The 9-weeks-long exhibition features the work of 18 international artists and activists and materialises the ideas (from open questions to proposals) that emerged from the collective research and the online internal and public discussions which animated the project in the past months – especially during the months of lockdown. It opens and closes with an INVOCATIONS programme of performances, and is accompanied by a series of workshops and seminars with young students and schools, and with vulnerable communities. A publication, printed and online, will chronicle and wider discuss the collective investigation, and the transpositioning on air – on the radio platform SAVVYZΛΛR – will echo and expand the reasoning, the pondering, and the practices entangled with the project.

Cities, spaces in general, give to their dwellers and visitors mnemonic tools that help people remember and navigate them. These tools can be wide-ranging from remarkable buildings like churches or skyscrapers, to monuments, prominent sculptures and many other outstanding structures. Besides the obvious structures like the Gedächtniskirche or the Fernsehturm at Alexanderplatz, people that have visited Berlin in the last years, and even the city’s residents, have taken with them an unlikely feature that has been marked in their memories: the image of young and old people alike with a sack hanging from one shoulder, a torch in one hand and the other digging deep in the trash containers of the city in search of food, drinks, or mostly empty bottles to be returned for deposit (Pfandflaschen) Pensioners, students, young and old, people of all walks of life whose main income is from the Pfandflaschen they pick up everyday, whose main course of the day is the leftovers they find in the trash; whose main career is begging, and whose space of repose in the night are the streets of Berlin.

The question that arises is how could one of the strongest economies in the world, Germany, afford to treat its old and young as such? How could one of the most affluent societies not have food and shelter for all its citizens? How could a country of egalitarianism cultivate such a yawning gap between the rich and the poor? Until now, the advocates of capitalist economy have told us that the more we produce, the more we consume, the more we work, the better our lives will be. So what happened to the dreams dreamt by the architects of neoliberal economy? What happened to the dreams dreamt by the believers and disciples of free economy and the social state? It is difficult to reconcile the terms poverty and Germany, especially for some of us who have seen poverty before, elsewhere; but though the poverty in Berlin is modelled to be unseen, unperceived, unfelt, it is there in terms of the relative wealth of the society. How many people have the courage to look into the eyes of the homeless beggars who approach you in the U-Bahn asking you for money or food? Do we actually see them? Hear them? Care for what has happened to them? Do we consider their human suffering? Or do we move to the next wagon when we smell them?

Today, and in these months, these thoughts have gained an unprecedented and unforeseen significance. As Covid-19 spread around the world, and markets suddenly crashed, we witnessed and confronted ourselves, probably more clearly than ever, with the pitfalls of capitalist economies. We witnessed the vulnerability of bodies and infrastructures within such economies, and of course the frail limits of European and global solidarity.

The project RAUPENIMMERSATTISM [1] grapples with what affluence, growth and degrowth have meant, mean, and will mean to societies, problematising the myth of endless consumption and our cultures of affluence, in particular within the context of Berlin and Germany. We look at the paradoxes of a space like Germany and other “strong economies”, whose strength more often than not relies on the weakness of others. Since the inception of the project – one year ago – what we wanted to understand is the sudden possibility of volatile change, the violence embedded in the structures we inhabit so precariously, and the possibilities or impossibilities of a sustainable future.

The project aims at understanding the machinations, the technologies, and the cultures that allow for, and enable such a rich society, wherein production and consumption are ever rising but where there are also people in the so-called middle of the society scared of an eminent poverty, while some have to feed from the trash cans of the city and others sleep on the pavements without a roof over their heads.

The brick wall facing SAVVY Contemporary just below the S-Bahn station Wedding hosts Mansour Ciss Kanakassy’s Ideogramme de l'Espoire, which acts as a leeway to introduce the exhibition. Silk screen designs manifest as political posters, advertising a newly imagined, pan-African currency which unveils the financial entanglements of neocolonialism as much as proposing new images for a possible future.

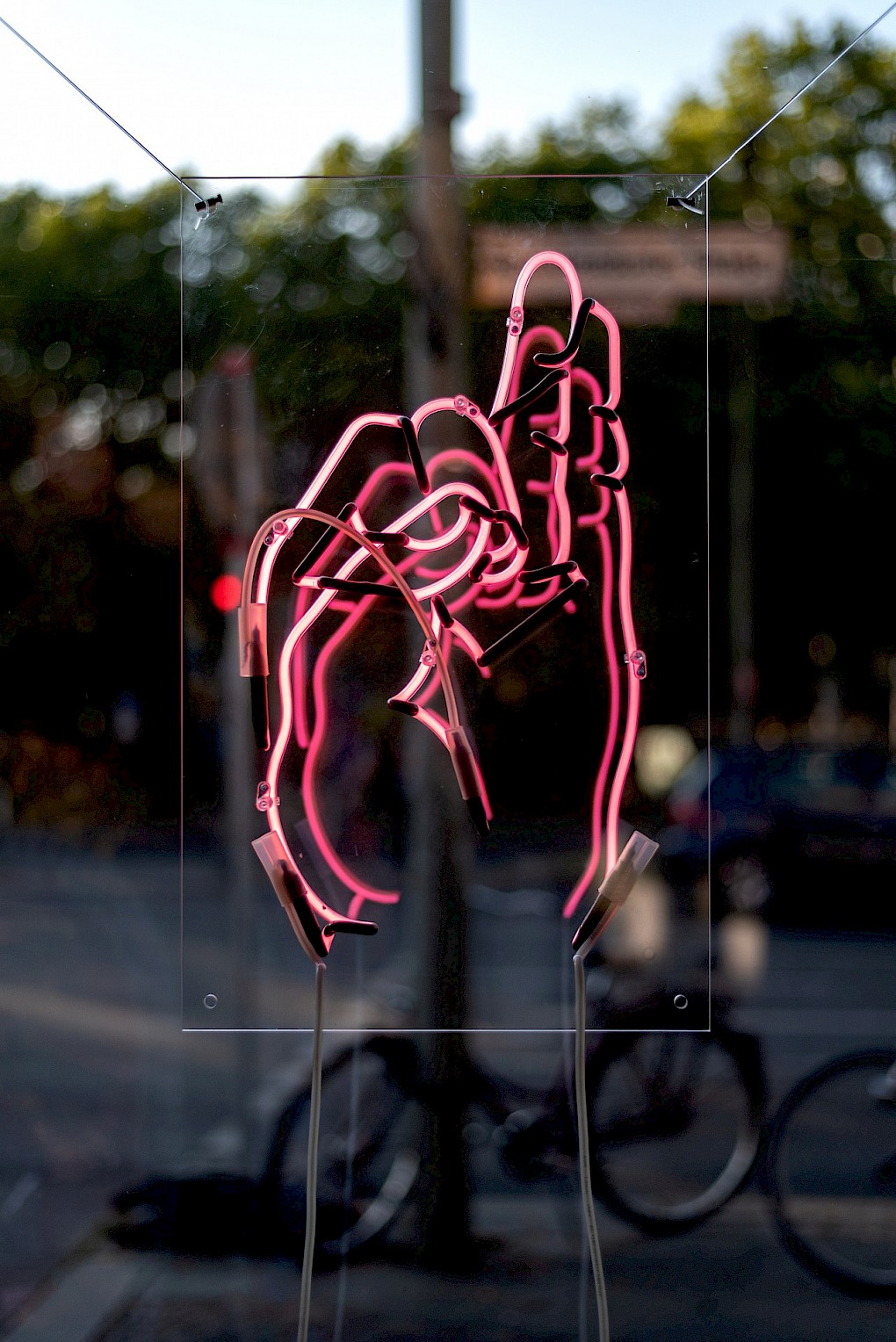

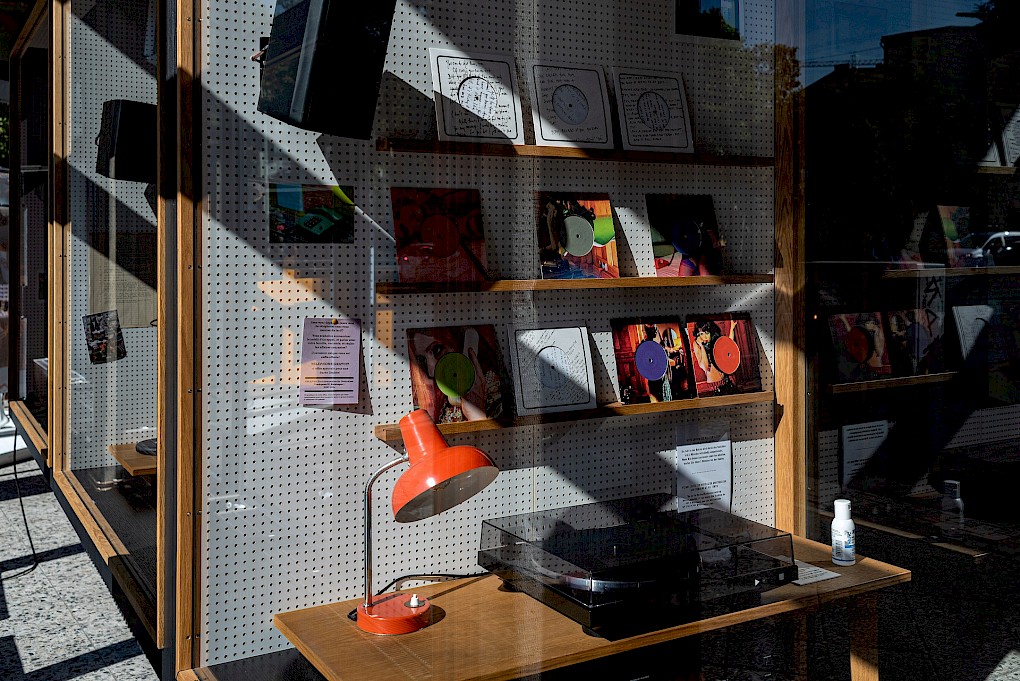

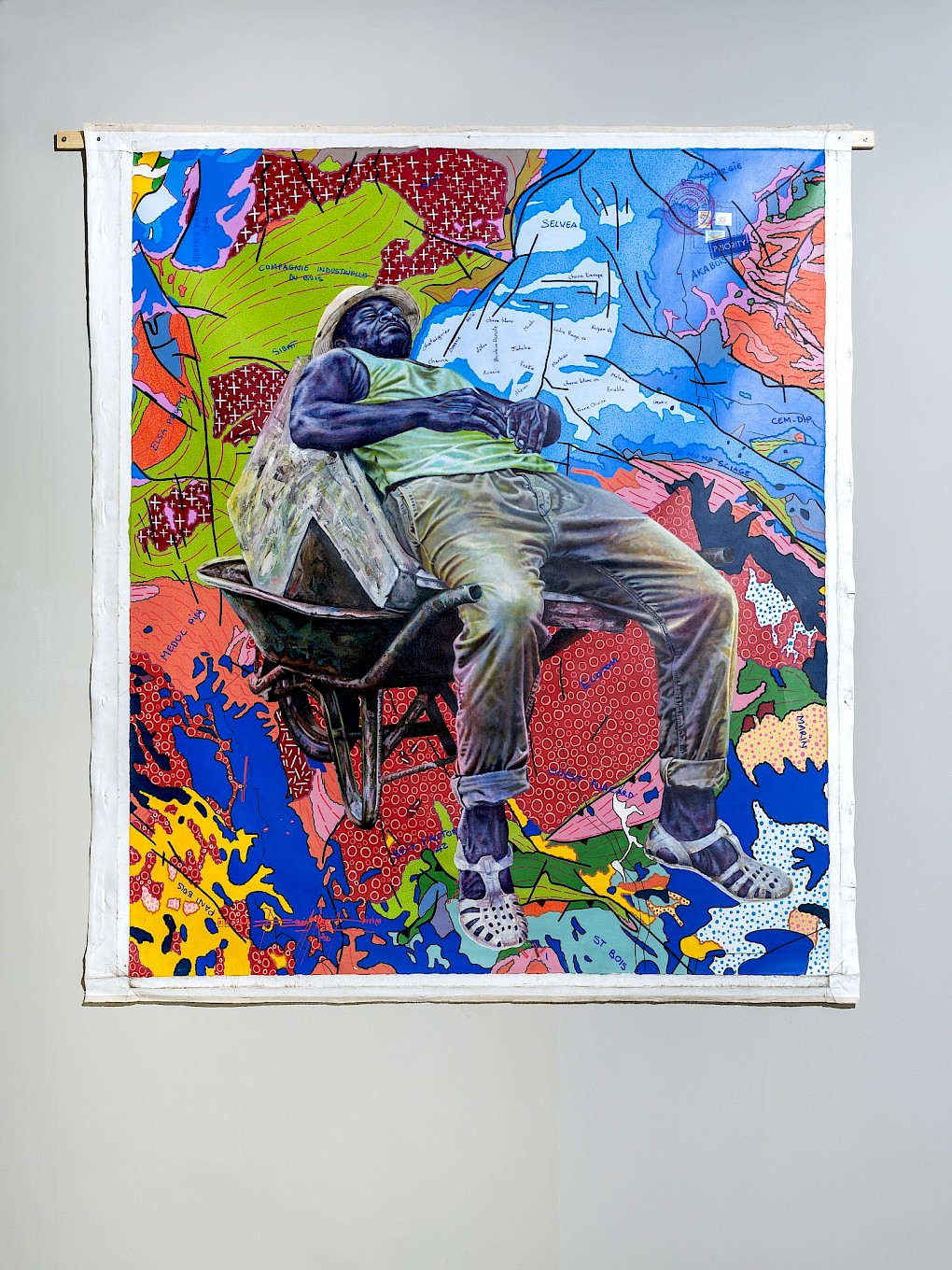

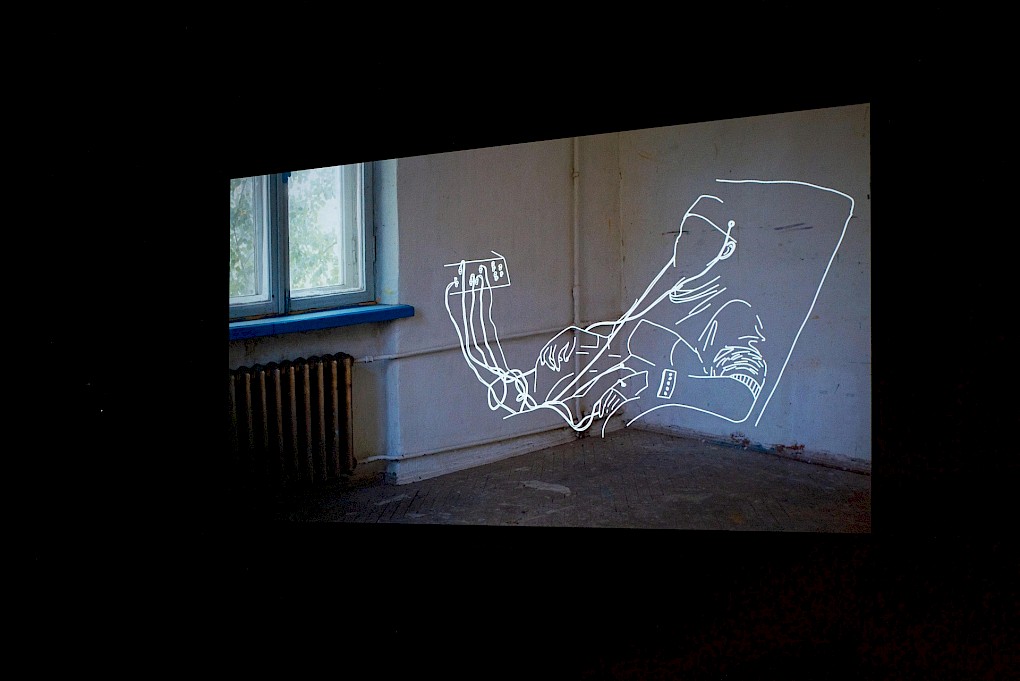

Inside the space, we are greeted by Sol Calero’s work Pica Pica, a layered installation referring to a Venezuelan legend and site of granted miracles. The installation is a moment of omen, of contemplation on how desires may be given form. Phil Collins’ listening booth comes from a collaboration with guests of GULLIVER survival station for the homeless (Cologne), where a phone booth with a free line was installed, available for unlimited local and international calls on the agreement that the conversations would be recorded and anonymised: the selected material of songs created as a response on vinyl in the booths come from a group of international musicians. Killing us Softly is a work by Krishan Rajapakshe that consists of images and mannequins focusing on the plight of around 6,000 factory workers in Cambodia who protested in 2014 by using their one hour break time to demand from Western brands, such as C&A and H&M, a 177€/month minimum wage. Laylah Amatullah Barrayn presents an excerpt of portraits taken in New York and Minneapolis that document the lived experiences of Black Americans during the double crisis of the current Covid-19 pandemic, and the simultaneous uprisings against systemic injustice and racism. Nasan Tur’s Variationen von Kapital commissioned a computer scientist to create a formula, which enabled the computer to generate all possible spelling variations of the word “Kapital”, calculating more than 41.000 possible variations: where Nasan then transferred the variations of the word with a brush on handmade paper; the show features 100 of a current number of 800 these unique handwritten pieces. Our structures of pandemic-precarity are echoed in Minerva Cuevas’s film El Pobre, El Rico y El Mosquito. In it, a young child reads a poetic fable by Spanish socialist author Tomás Meabe, as a mosquito hovers behind him: a tale is told of a callous rich man who felt he had nothing in common with a poor man living across from him; in the end both die of the same virus a mosquito carried. Sarah Entwistle unravels, vandalizes, and problematizes her late grandfather’s archives. He was an architect whose professional practice is deeply conflated with the imagery of the female nude. Sarah Entwistle is working in ongoing partnership with Moroccan weaver Kebira Aglou – extracting and magnifying scars and traces of her grandfather’s process to rewrite his architecture from a perspective of care, questions, and feminist lenses. Anton Kats’ Vostok 7 is an artistic study of the Vostok Program of Soviet Space Travel. In this semi-fictional narrative on the colonization of space, sound and listening serve as dynamic methods of self-reflection, politics and processes of inner and outer-space exploration, and critiques of contemporary colonial forces of marginalizing political segregation. The work will be activated by the space traveler ILYICH through a series of performances and performance-lectures, explorиng the de-colonial potential of listening. Yasmin Bassir’s Ein Werk Ohne Ende (A Work Without End) is comprised of handmade clay objects that are repetitive, yet distinct, lifelong developments and daily acts of creation: she sometimes integrates them visibly into chosen landscapes and leaves them behind or buries them to dissolve back into nature after time; bringing to mind the ways in which everyday labor, production, and nature overlap with one another or move apart. Jean David Nkot's painting made for SAVVY Contemporary centers a female migrant worker with a shovel in her hand against a cartographic background, contemplating labor struggles and resiliency.

With tablecloths, Samira Hodaei looks into the painful history of Iran’s ties to oil money, which has not fostered social equity in the country: as means of resistance and justice-seeking, she works with the material that Iranian peaceful protesters implemented as they laid empty tablecloths in the streets, symbolizing their inability to feed their families and highlight the workers’ poor economic conditions. This bridges to the series I Have to Feed Myself, My Family and My Country… by Hit Man Gurung of ArTree Nepal. His photographs HAPPY NEPAL !!! PROSPEROUS NEPAL !!! addresses labour migration, a phenomenon prevalent in South Asian countries like Nepal, and reflects on Nepal’s rapidly changing socio-political and socio-economic landscape.

In the staircase leading to the basement, Daniela Medina Poch & Juan Pablo García Sossa’s Papel Soberano hangs above us aiming to be a site of empathy and support, while investigating the roles of papers: making tangible, sensible, and graspable the hardships of the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis by directing attention towards the unstable Venezuelan currency and the country’s wave of migration which has created generations with irregular statuses and undocumented children. In the basement, five of Cinthia Marcelle’s slow and poetic films show on loop, each relating to the myth of overproduction and its industries, the performance of power through the automobile, and how it relates to labour and consumption. LAGOM: Breaking Bread with the Self Righteous is a film by Lhola Amira which takes its title from the word pronounced laah’gom, the Swedish ethos of “not too much, not too little – just the appropriate amount”; it is an ongoing drama revealing various negotiations around the gaze and its relation to history, memory, political geography and material culture as well as footprints of colonialism and slavery. Stemming from a performance, Fallon Mayanja’s sonic piece traverses the nearby staircase with black archive textures, techno poetics, and stories of healing amidst burdened haunts and reclaimed memories.

Our aim is not to give the right answers, but to instigate possibilities of coming together, working together and finding ways of posing the right questions. The project is an effort to reflect on the myths of a consumer society, especially in times of advanced information technology and social media. It is a project that tries to understand the phenomenon of the “Flaschensammler”. It wants to make sense of and focus on this image, as well as its resonant sibling subjects standing in relation: laborers documented and undocumented working in unstable conditions. Those who must take jobs as cleaners, sex workers, caretakers, construction workers, factory workers and farm workers – who seek wherever possible to sustain livelihood when on the fringes of society due to gender, positions of migrancy, race, class, and other factors which systems historically and ongoingly restrict, hinder, or exploit. We think alongside members of society living in precarious positions, stark with slippery foundations and risks, where benefits and protections are often lacking. We look to this paradigm in order to address it, confront it, and share stories centering the plights coming from capitalist violence, instead of averting our gaze. We also ruminate on possible presents and futures of re-working, re-writing, and re-cycling individual and collective processes of solidarity and resistance.

If in the 1930s, the economic crisis (the so called Great Depression) created a fertile ground for the rise of fascist governments in Europe, in the second decade of the 21st century (during the so called Great Recession, and the financial crisis of 2008-9) the economic struggles for neoliberal sovereignty have been assisting the rise of the far right. Austerity policies have crafted the grounds for discriminatory social welfare Darwinism and national economic policies (a la “America First”, “Prima Gli Italiani”, and so on). And again, a primacy of economic support has been coupled to nationalist logics; pairing growth and nation.

Interestingly, the ranks of the European far right did not come anymore from the underprivileged and marginalised but also and especially from the middle class, the group most threatened by the aftermaths of the financial crisis. The consequences of that global financial bursting are still affecting our societies, where extremes of wealth and poverty have been fuelling plutocracy and “oligarchic domination” with dangerous forms of populism.

We still don’t know where this crisis is going to take us, but in this historic and unparalleled turning point, engaging with these cogitations is not just relevant, but fundamentally needed.

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung

CURATORial Team Elena Agudio, Antonia Alampi, Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock, Kelly Krugman, António Mendes, Arlette-Louise Ndakoze

MANAGEMENT Lema Sikod, Jörg-Peter Schulze

COMMUNICATIONS Anna Jäger

DESIGN Juan Pablo García Sossa

TECH Bert Günther and Björn Matzen

ART HANDLING Rey KM Domurat, Kimani Joseph, Stephan Thierbach

LIGHT Catalina Fernandez

NEW SAVVY SPACE DESIGN Ola Zielińska

ARCHITECTURE Max Dengler/Kombinativ

Photos Raisa Galofre

Funding This project is funded by the Senatsverwaltung für Kultur und Europa des Landes Berlin. ILYICH’s contribution is supported by Musikfonds.

Special Thanks to Jörg Heitmann/Silent Green and Andi Banz/ Kundschafter

RAUPENIMMERSATTISM takes its cue from the The Very Hungry Caterpillar (In German: Die kleine Raupe Nimmersatt), a children's picture book designed, illustrated, and written by Eric Carle, first published by the World Publishing Company in 1969.