Mercedes

How does the world breathe now?

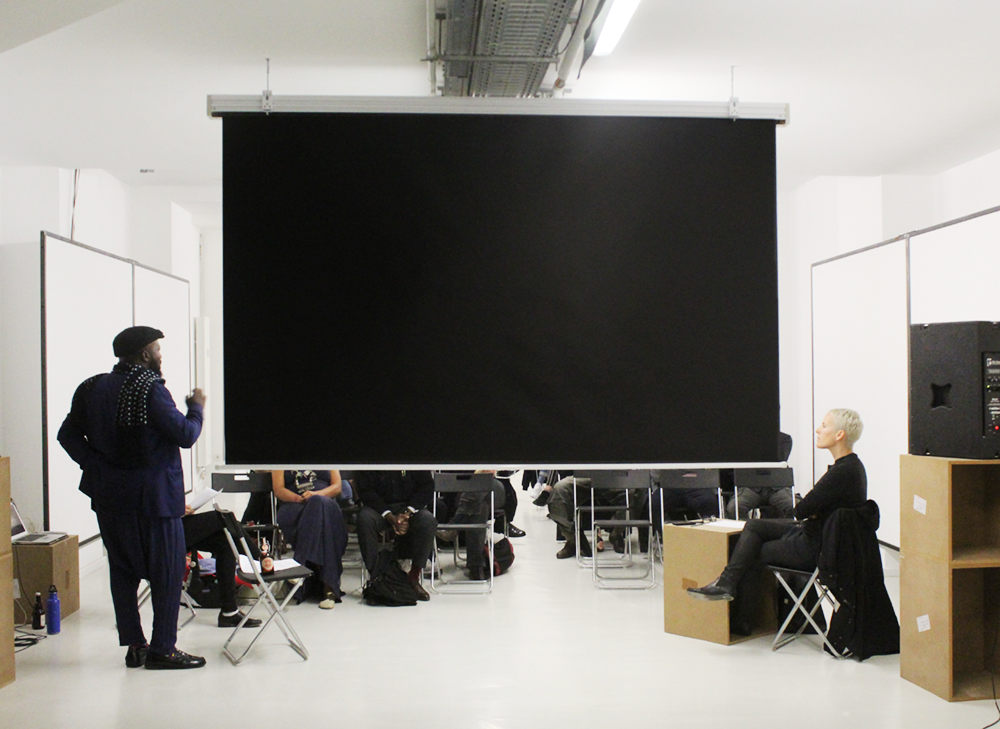

Session N°8 16.11.2016 19:00

With Malak Helmy

film Mercedes 105 minutes 1993

bY Yousry Nasrallah

Language Arabic with English subtitles

Mercedes, made in 1993, is the second film by Egyptian director Yousry Nasrallah. The film is set in Cairo in 1990, almost ten years into Mubarak’s presidency. It is a year often cited as marking the transformation of the institutional fabric of the Egyptian economy into a truly market-oriented economy. Aggravated by a global recession, diminishing remittances from migrant workers in the Gulf–because of the impending crises there and the drop in tourism due to growing terrorist attacks locally–the Egyptian economy was lead into major privatization. Trade reforms and cuts in public spending became a condition to receiving bail out funds from the IMF and World Bank that year.

Mercedes is set against the backdrop of the dark triumphs of Liberalism–perhaps typified through its most symbolic commodity from which the film takes its name, which is also personified into a character that the protagonists are searching for in order to receive an inheritance. It weaves a satirical image of the dissonant social and political realities of Egypt in the 90s and paints them into an extremely surrealist image of its present. In it, Liberalism strolls around the dashed dreams of Communist bloc, Islamism is on the rise, the Persian Gulf is burning out, and football becomes a sensuous and tense mesh that roams the city that is otherwise connected by the intimate and violent networks of drug and organ trafficking and sexual relations–straight, gay and deviant–weaving through. Lost and eccentric characters are choreographed by this time roam around this absurd reality that is both beautifully filmed and saturated in colour.

The film unfolds through an eccentric family–remnants of old-world aristocrats, their step wives and their children oddly placed in their present. Mostly it hinges on the story of two men who teeter on the margins–half brothers–who have rejected their social positioning and try to escape the violence of their class through different means: one is Nubi (Zaki Fateen Abdel Wahab)–the main protagonist of the film: a Communist who falls into a strangely oedipal relationship with a bellydancer (Youssra) who is the mirror image of his mother (also performed by Youssra) who had checked him into a mental institute because of his political affiliations. The other is Gamal, his homosexual half brother, an artist, who decides to affiliate with the Muslim Brotherhood, spends time in cinemas and dens or with football fans roaming the city.

The beauty of Nasrallah’s work, which is very much articulated in the unique characters in this film, is his depiction of outsiders and vagabonds born out of the incongruities of the nation. He opens up an imaginary and an image of complications of love and sexuality outside of gender norms and normalizes them in his writing, in a manner rarely seen in Egyptian cinema. Outside of the uniquely layered, complex image of gay love and homosexuality in the landscape of Cairo, of which there are few precedents to compare, it is fascinating to note that the drug dealing and most noted sexual encounters are not performed by men, but by the female characters in the film.

Malak Helmy’s personal affiliation with the film began by way of a friend some years ago. Perhaps it is the way in which it embraces the madness of so many narratives at once or perhaps it is the characters flourishing within it that makes the film so rich to revisit over and over again. In either case, it is a fine example of the wave of experimental, somewhat surrealist films of its time. Its relevance today is still great, with Egypt entering into a new deal with the IMF, it is interesting to look back at that moment in 1990s when this all began. Also, too, to revisit the earlier of one of Egypt’s best directors.

Malak Helmy is an artist working between video, sound, text, objects and the architectural sites in which they’re hosted. Writing into areas such as digital dust and state collapse, leisure communities and carbon compounds, her work fuses personal memory with social and political developments, blurring lines between real and fictionalised sites or events. She is currently co-curating Meeting Point 8: Both Sides of the Curtain, whose second chapter takes place in Brussels in December 2016. Her work has been exhibited in places such as Camera Austria, the 64th and 63rd Berlinale Forum Expanded, CCA Singapore, the 9th Mercosul Beinnial, EVA International and Gwangju Biennials, Alamanac Projects, London; Aspen Art Museum, and Beirut in Cairo. Her writing has been a part of The Cyprus Pavilion Bienniale Arte 2015 reader; oo-oo.co; Happy Hypocrite; Log–Journal for Architecture and Urbanism and Ibraaz. She co-initiated Emotional Architecture, a writing and publication project. And is co-editor of Stationary02.

Support This screening is kindly Supported by Zawya Distribution