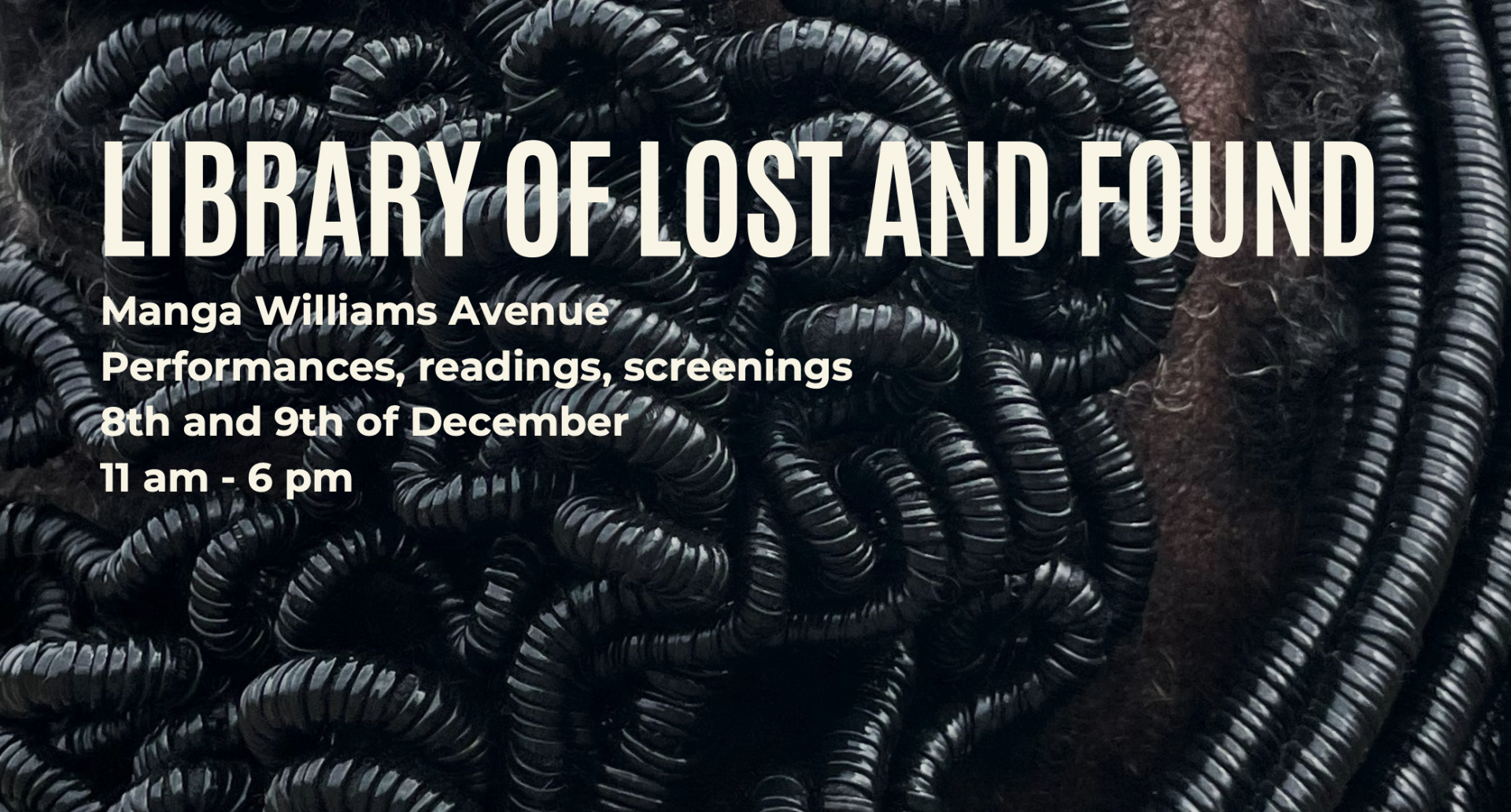

Library of Lost and Found

Eröffnung des SAVVY Kwata Limbe

08.–09.12.2023

Ort Manga Williams Avenue, Limbe, Kamerun

WE IN PROGRESS ist ein audio-visuelles Kunstprojekt der Initiative BLACK DADS GERMANY in Zusammenarbeit mit Yero Adugna Eticha (Black in Berlin). Gedacht als reines Monolog-Konzept und in Anlehnung an mündliche, afrikanische Traditionen bricht es mit der schnelllebigen, impulsiven und oft von Hassreden geprägten, ungezügelten Diskussionswelt im Internet. Die Arbeit konzentriert sich auf die autobiographischen Lebensgeschichten Schwarzer Väter in einer mehrheitlich weißen Gesellschaft in Deutschland und beleuchtet (Lebens-)Geschichten Schwarzer Väter, die sonst kein Gehör finden. Einige der Schwarzen Väter leben seit Jahrzehnten in Deutschland oder sind hier geboren, aufgewachsen und sozialisiert worden. Ihr Leben ist bisher nicht ausreichend dokumentiert – weder in Filmen noch in Theaterstücken oder Büchern.

WE IN PROGRESS schafft sichere Räume für Schwarze Menschen und gleichzeitig Grenzräume für weiße Verbündete. Räume, in denen es eine Rückbesinnung auf die verlorene Tugend des Zuhörens gibt. Die empathische Kraft der interdisziplinären Arbeit wird durch die Porträtfotografie von Yero Adugna Eticha verstärkt. Als Zeitkapseln archiviert, ermöglichen wir zukünftigen Generationen einen Einblick in das Leben der Schwarzen Väter. WE IN PROGRESS schafft realistische, greifbare und empathiefördernde Räume voller Schwarzer (Lebens-)Geschichten.

Wir freuen uns, mit Euch die Lebensgeschichte von Anthony Owosekun, Vater, Pädagoge und Gründer von EMPOCA & DE_CONSTRUCT, teilen zu können. Anthony wird über sein Leben als Schwarzer Vater sprechen, über seine Zeit als Schwarzer Pfadfinder, seine Erfahrungen in der Natur und seine Liebe zu seinen Kindern. Eine Stimme – eine Lebensgeschichte.

WE IN PROGRESS wurde auf der Architekturbiennale in Venedig 2021 ausgestellt und war Teil des Kunstwerks "100 Ways to Say We", das auf der Online-Plattform "100 Ways to say We. Ein Archiv der Zukunft" veröffentlicht wurde. 2023 wurde WE IN PROGRESS beim Dortmund Goes Black Festival im Theater Dortmund, auf dem Liebe und Geld Festival des Schauspiel Dortmund, sowie beim BLACK OUR STORY MONTH bei Each One Teach One e.V. gezeigt.

Mehr Informationen zu BLACK DADS GERMANY und dem Projekt WE IN PROGRESS findet Ihr hier: www.black-dads-germany.com.

In this archival endeavor we collect for the collective, we gather for a gathering, and we search and find to be sought out and found. We call upon everyone to expand on what we have previously understood to occupy the role of the “author” and to re-shift our collective focus onto the varied forms of knowledge preservation and transmission which had thrived for generations before their eventual subjugation. Might there be space for others on the bench upon which the African “author” sits?

It is essential that, while we collectively sense the importance of the need to focus on African authorship on the African continent, we cannot ignore the irony as it often shows a hidden truth. The written form is a method which has been assigned to western culture, often on the part of Africans, but it is a form that has long been embedded in our society. Ours is home to the oldest and largest collections of ancient writing systems as well as the world’s first identifiable proto-writing. Writing is a method which has had differing degrees of importance for different generations of Africans and its relevance for this generation is a subject of study at SAVVY Kwata.

The period of colonization, often marked by the occupation of most of the continent of Africa by the imperial governments of Europe and in pursuit of wealth and racial domination is an obvious marker, yet the post-independence period of the 50s and 60s provided Africans with a great number of writers, poets, novelists, archivists and theorists – authors who have necessarily complicated what Europe preferred to label as a momentary phenomenon – locked in time. We look towards our own writers to help us understand our history not simply in an effort to reclaim narrative power from the hands of the oppressors, but also to find ourselves beyond the continuous hold of a continental trauma.

Who then are these authors? Our very understanding of authorship must also be centered around a question of legibility. For some, there is a clear legibility in Frantz Fanon, who alerted us in his seminal work The Wretched of the Earth, of the French response to the situation in Algeria and of Europe’s increasing need to shape the decolonizing process. “Quick, let's decolonize. Let's decolonize the Congo before it turns into another Algeria. Let's vote a blueprint for Africa, let's create the Communaute for Africa, let's modernize it but for God's sake let's decolonize, let's decolonize.” [2] Chinua Achebe too was prescient in his suspicion of the organized nature of the handover of government as he pointed out that “The British clearly had a well-thought-out exit strategy, with handover plans in place long before we noticed.” [3] If Chinua Achebe, the great novelist of the “post-independence” period had not noticed, does that automatically mean that no one else had? We are fortunate however that while the great writers of Africa can help us in our quest to understand ourselves and our history, we are also blessed with a wealth of storytellers that speak with different legibilities. In reshifting our collective focus to the literary gifts that Cameroon and the African world has left and continues to grant us, it is vital that we also look beyond those who have mastered the written form. It is within these other articulations of knowledge which are transmitted through cultural and traditional practices that we can begin to make sense of who we are, and perhaps even where we are going. We must make more room on that bench upon which our African author sits.

We are honoured to welcome you to SAVVY Kwata’s inaugural opening of the Library of Lost and Found.

Support SAVVY Kwata is generously supported be the Open Society Foundation.

Photos Grace Dorothée Tong

“Ancient African Writing: Ancient Writing, Ancient Writing Systems, Ancient African Scripts.” TaNeter.org, http://www.taneter.org/writing.html (accessed 6 December 2023).

Frantz Fanon. "On Violence", The Wretched of the Earth, 1961.

Chinua Achebe. There Was A Country: A Personal History Of Biafra, 2012