Eyes of Stone

How does the world breathe now?

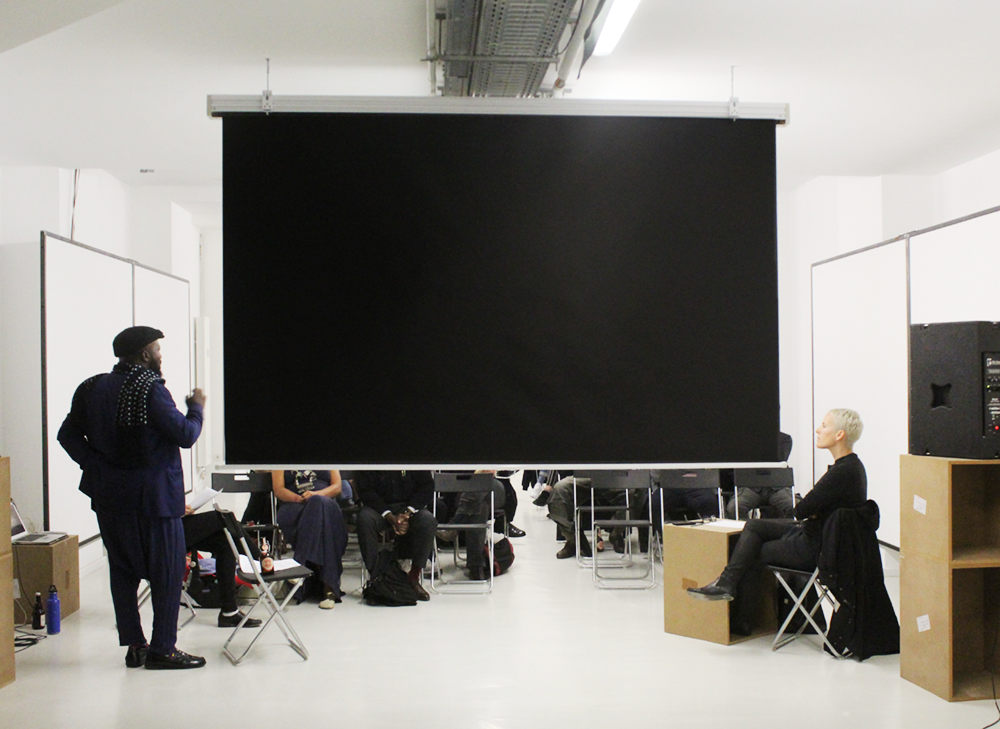

Session N°19 12.04.2017 19:00

With Chus Martínez

film Eyes of Stone 1990 91 minutes

by Nilita Vachani

Language Mewari and Hindi withEnglish subtitles

Chus Martínez on her selection of Eyes of Stone forhow does the worlD breathe now?:

In December last year I travelled to India to meet Tejal Shah, artist, filmmaker and a good friend. They had spent some time in the past years reflecting on Buddhism and on its non-dualistic views on reality. We were discussing how Tejal, in turning towards ancient Buddhist views of knowledge, was “forcing” tradition to think about gender in an unexpected way. Looking at both their practice and personal life, I saw how the Buddhist concept that rejects the idea of an intrinsic characteristic of a fixed, absolute “self” (essence) which creates a definitive identity of an individual, was merging with the queer idea that there is no inherent, necessary characteristic that defines personhood and codes people as one or the other gender. It was Tejal who showed me Eyes of Stone by Nilita Vachani and it is for this reason that I wanted to do the same and screen this film as part of SAVVY Contemporary’s film series. I am unaware if my presentation can again channel their enthusiasm about what Nilita Vachani is trying to convey in a film that, in observing certain rituals in the temples, discovers the life of a woman possessed by a spirit.

The film tells the story of a nineteen-year-old woman, Shanta, who was married off at the age of 10 to Nanda Lal, a truck driver 10 years her senior. The film, though, does not “portray” their story, but observes it. Vachani follows her subject through the village of Bhilwara, in Rajasthan, to discover how spirit possession is a language that embodies a mode of resistance in women. It helps them to define a space for their bodies, their voices, and, at the same time, avoid the naturalized ways in which tradition expresses power between genders. After reading Sudhir Kakar’s text on possession, Nilita Vachani decided to visit temples where rituals of healing were performed, and found out that most of the possessed were woman. She started observing, conducting field research on the subject, which lead her to disagree with those that saw possession as only a psychoanalytical desire for the father figure.

I think that the film, and its history of censorship after its release, allows us to engage in a conversation about the space of women, the languages we use to claim freedom, and also about life within misogynistic times.

Chus Martínez is the Head of the Art Institute in Basel, a writer and a curator.